Advertorial

Moderné plynové technológie: Efektivita a inovácie pre 21. storočie

Sumarizácia najdôležitejších inovácií, ktoré redefinujúcich využitie tohto energetického zdroja.

Utesňovanie spodných stavieb pomocou hydro-aktívnej fólie AMPHIBIA.

AMPHIBIA 3000 GRIP 1.3 od spoločnosti ATRO predstavuje modernú hydroizolačnú technológiu, ktorá spája vysokú odolnosť,...

Dekarbonizácia individuálneho vykurovania domácností – Green Deal evolučne a nie revolučne

Ambiciózne plány EK narazili na ekonomické možnosti domácností v jednotlivých členských štátoch –...

Minimalistické dvere IDEA – technická precíznosť a čistota prevedenia

IDEA DOOR od spoločnosti JAP prináša do interiéru čistý minimalistický vzhľad vďaka bezrámovému riešeniu a precíznej...

Schell Vitus – osvedčené riešenie pre sprchy a umývadlá vo verejnom sektore s viac ako desaťročnou tradíciou

Nástenné nadomietkové armatúry Vitus sú mimoriadne vhodné pre rýchlu a efektívnu...

Kompozitné okná predstavujú súčasnosť a budúcnosť

Okenné profily z kompozitného materiálu RAU-FIPRO X od spoločnosti Rehau sú v porovnaní s tradičnými plastovými profilmi mnohonásobne...

Myotis - stoly 2025

Najnovší sortiment stolov pre zariadenie interiérov...

Priemyselné sklenené priečky Dorsis Digero: svetelné rozhranie pre moderné interiéry

Spojenie moderného dizajnu, funkčnosti a svetla do harmonického architektonického prvku.

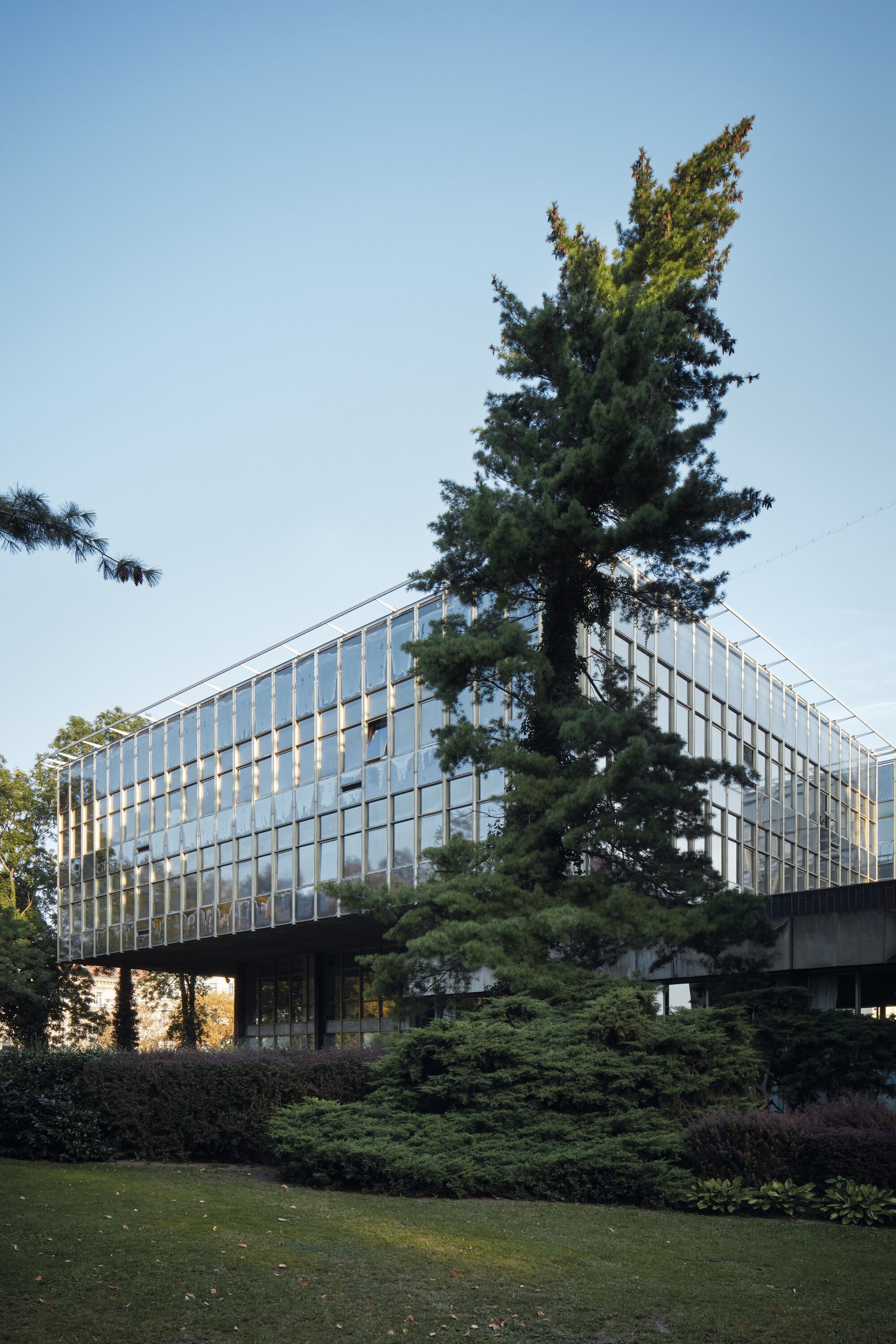

Význam prirodzeného svetla pre moderné a flexibilné pracovné prostredie

Kancelárska budova Baumit v slovinskom Trzine prešla premenou na moderné a udržateľné pracovisko. Architekti kládli dôraz...

Konferencia Xella Dialóg predstaví novinky a trendy v stavebníctve

Mottom šiesteho ročníku on-line konferencie odborníkov Xella Dialóg je Efektívny návrh budov 2025+: zmeny a riešenia

Murovací robot WLTR stavia svoj prvý dom na Slovensku

Robot WLTR predstavuje moderný prístup k murovaným konštrukciám. Vďaka automatizácii dokáže rýchlo, presne a bezpečne realizovať...

Nová éra bezpečnosti s I-tec Secure od Internorm

Okrem bezpečnosti majú okná aj elegantný vzhľad, pretože nie sú viditeľné žiadne uzamykacie časti kovania.

Skryté zárubne JAP – intenzívny zážitok z bývania

Dvere MASTER v skrytej zárubni AKTIVE je možné vyrobiť až do výšky 3 700 mm

Tienenie namiesto klimatizácie

Internorm stavia na energetickú efektívnosť a inteligentné tieniace riešenia.

BigMat International Architecture Award 2025 - vybrané diela

Slovensko vo výbere zastupuje šesť realizácií.

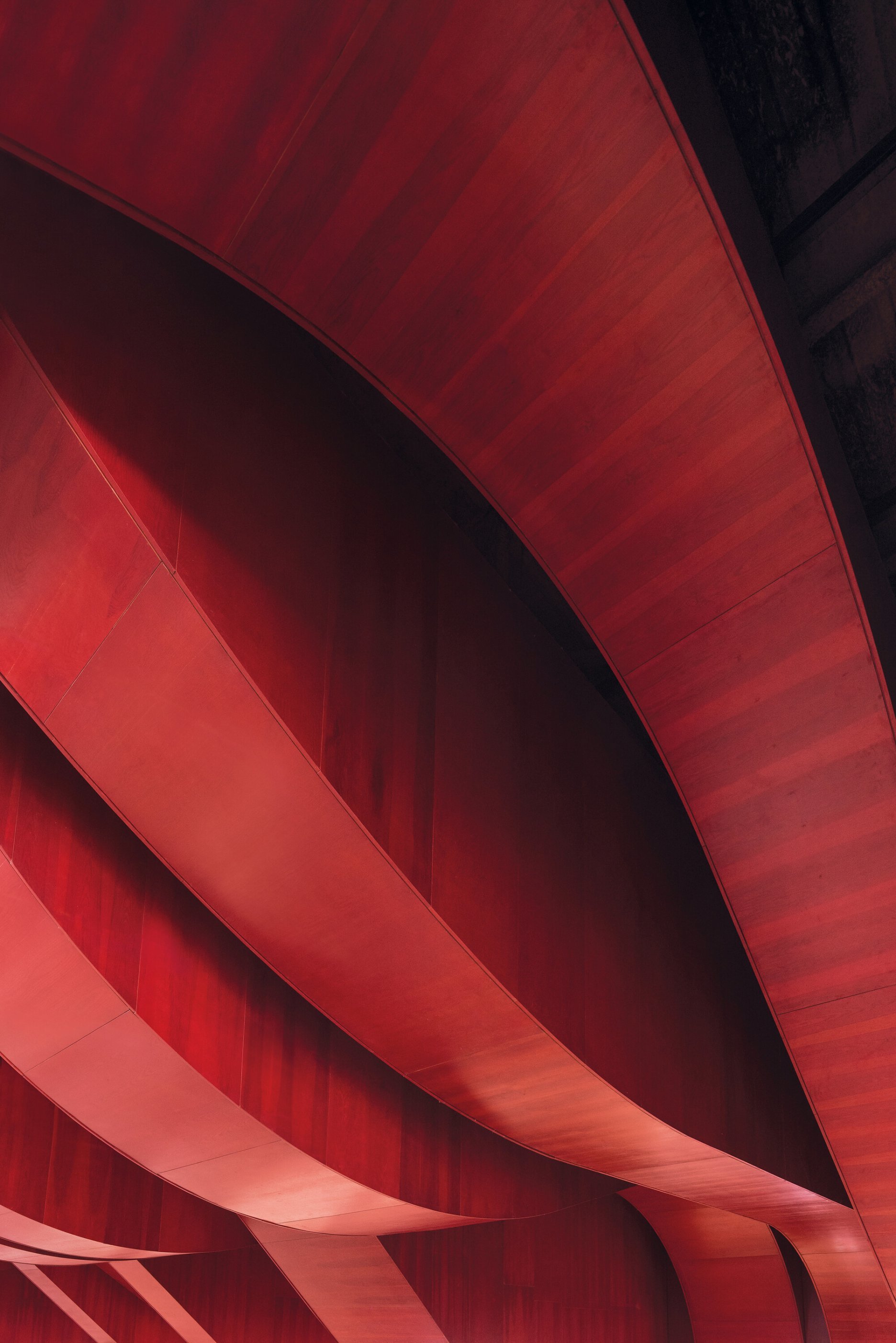

Praha brutálně krásná. Mimořádné stavby postavené v Praze v letech 1969-1989

Fotografie Tomáša Součka, Petra Poláka, Filipa Šlapala a BoysPlayNice vznikli pre knihu Praha brutálně krásná, ktorá predstavuje mimoriadne stavby z rokov 1969 - 1989 spolu s významnými osobnosťami spojenými s architektúrou, medzi ktoré patrí Michaela Janečková, Pavel Karous, Petr Klíma, Rostislav Koryčánek, Petr Kučera, Adam Štěch a Vladimir 518. Editorem knihy je Ondřej Horák.

Nájdeme tu napríklad neprehliadnuteľný objekt Novej scény Národného divadla, umelecké diela vo verejnom priestore z doby normalizácie, alebo obchodné domy Kotva a Máj...

Impulzom pre vznik knihy bolo búranie hotelu Praha v roku 2014, ktoré vyvolalo vlnu nevôle podobne ako prípad bratislavského Domu odborov...

In January 2014, hotel with the symbolic title Praha starts to irrecoverably disappear from the city landscape. For a long time, industry professionals as well as the general public, gradually realized the extraordinary situation that transcends the topic of architecture. The demolition of the hotel originally built for Communist bigwigs and international government delegations sparked a debate on the necessary protection of these types of buildings.

Perhaps for the first time, inhabitants of more than just the capital have come to appreciate the architectural, artistic and socio-historic value of such objects. What irritated the public in the first place was the way the hotel was demolished, because it was almost identical to the one represented by the almighty Communist government.

Evaluating architecture is not easy. The tragic story of Hotel Praha is by far not only the question of beauty and ugliness, function and uselessness, not even the size. Maybe it was not much about the hotel as such. Critics of the demolition were outraged by the fact that out of sheer caprice, any owner could make a building disappear forever. It is enough to label it “not functional” and/or “ugly” and there is no existing way to avoid its demolition. Above all – if such intention affects the history of any one building there exists no guarantee that it will not happen again.

Hotel Praha symbolizes another significant question our society has been dealing with since the beginning of the Nineties: Is it at all possible to remove the label “Communist barrack” from buildings that were initially created with the purpose of representing the “one-party government” of the socialist Czechoslovakia?

One can understand the older generation quite well that the house of socialist Federal Assembly will be forever linked to the unanimously voting Communist Party MPs. Appreciation for the architectural solution of Žižkov TV Tower will be equally difficult for the locals, who observed the vans carrying Jewish tombstones, multiple hundreds of years old, away from the original graveyard and to a dumping ground. Nevertheless, today it is clear that a certain amount of time is necessary to clear off the ideological layer. And then only pure architecture and its function remains.

Provocative dimensions – not typical in Prague – and dominant size go beyond the regular and respected criteria. These indeed present other significant reasons for contempt of such architecture. Bold but also forced in a silly way, elegant but also hulky, monumental but also heavy. But especially big. Communist power is definitely not discreet and its ideology often interferes in ordinary people’s lives and crushes them. This is why these “brutal” buildings provoke so much. Such architecture is necessarily perceived with a certain dose of skepticism. It is part of the architecture as much as an interest rate that needs to be paid.

Since the fall of Communism in Czechoslovakia, people have been trying to find a way to deal with this kind of architecture. The first reaction is to try to get rid of the remains, demolish them, repaint or at least rename them. A lack of any protection for these objects and installations made them a simple target. Architecturally valuable constructions are being removed from the urban space without a proper replacement.

Sculptures, objects, and architectural installations disappear from city parks and housing estates. Exquisite interiors and elements of design and applied art inside many buildings are irretrievably destroyed. A number of objects are reconstructed beyond recognition. It will take some more time until the loathing projected into the walls will transform into respect and understanding.

Buildings from the 70s and 80s, from the “tough,” then “creeping,” and eventually maybe even “consoling” normalisation became the centre of attention for the public that long regarded them as ugly. Society starts to realize their original beauty and courage, with which they were designed. Maybe another reason is that the contemporary architecture does not offer any other interesting alternatives in Prague. In any case, the time passed since their creation can suddenly give us more.

In fact, the buildings are not only the bearers of interesting and bold architecture by distinguished personalities. We tend to forget a lot from our past. These objects, however, do not allow this, they are part of our collective memory. Our past. Moreover, they are beautiful. Brutally beautiful.

- Horák, O. Prague Brutally Beautiful: Exceptional buildings constructed in Prague between 1969 and 1989, Prague, Scholastika, p. 13-14

Séria fotografií venovaná dielam z rokov 1969 -1989:

Praha brutálně krásná.

Mimořádné stavby postavené v Praze v letech 1969-1989

Vydavateľstvo: Scholastika

Autori:

- Ondřej Horák, editor, autor

- Michaela Janečková, autor

- Pavel Karous, autor

- Petr Klíma, autor

- Rostislav Koryčánek, autor

- Petr Kučera, autor

- Adam Štěch, autor

- Vladimir 518, autor

Spolupráca:

Grafický dizajn - Matěj Činčera, Jan Kloss

Knižný dizajn: OKOLO

Doplňujúci materiál: Tereza Fišerová, Matěj Hošek, Ondřej Brody, Evžen Šimera

Fotografie: Tomáš Souček, Petr Polák, Filip Šlapal, BoysPlayNice